in the beginning, what was the major challenge related to placing digital images on cd media?

8.2 The History of Movies

Learning Objectives

- Identify cardinal points in the development of the motion picture industry.

- Place key developments of the motion picture industry and technology.

- Identify influential films in movie history.

The movie manufacture as we know information technology today originated in the early 19th century through a series of technological developments: the creation of photography, the discovery of the illusion of motility by combining private still images, and the report of human and creature locomotion. The history presented here begins at the culmination of these technological developments, where the thought of the flick as an amusement industry first emerged. Since then, the manufacture has seen extraordinary transformations, some driven past the creative visions of individual participants, some past commercial necessity, and still others past accident. The history of the cinema is complex, and for every important innovator and movement listed here, others take been left out. Nonetheless, after reading this section you will understand the broad arc of the evolution of a medium that has captured the imaginations of audiences worldwide for over a century.

The Beginnings: Motion Pic Technology of the Late 19th Century

While the feel of watching movies on smartphones may seem like a drastic divergence from the communal nature of film viewing every bit we recall of it today, in some means the small-format, single-viewer display is a return to film's early on roots. In 1891, the inventor Thomas Edison, together with William Dickson, a young laboratory assistant, came out with what they called the kinetoscope, a device that would become the predecessor to the move picture show projector. The kinetoscope was a chiffonier with a window through which private viewers could feel the illusion of a moving paradigm (Gale Virtual Reference Library) (British Pic Classics). A perforated celluloid film strip with a sequence of images on it was rapidly spooled between a light bulb and a lens, creating the illusion of motion (Britannica). The images viewers could see in the kinetoscope captured events and performances that had been staged at Edison's film studio in East Orangish, New Jersey, specially for the Edison kinetograph (the photographic camera that produced kinetoscope moving picture sequences): circus performances, dancing women, cockfights, boxing matches, and even a tooth extraction past a dentist (Robinson, 1994).

Figure 8.2

The Edison kinetoscope.

todd.vision – Kinetoscope – CC BY 2.0.

As the kinetoscope gained popularity, the Edison Company began installing machines in hotel lobbies, amusement parks, and penny arcades, and soon kinetoscope parlors—where customers could pay around 25 cents for admission to a banking company of machines—had opened around the country. However, when friends and collaborators suggested that Edison find a mode to project his kinetoscope images for audience viewing, he apparently refused, claiming that such an invention would be a less profitable venture (Britannica).

Because Edison hadn't secured an international patent for his invention, variations of the kinetoscope were soon being copied and distributed throughout Europe. This new class of entertainment was an instant success, and a number of mechanics and inventors, seeing an opportunity, began toying with methods of projecting the moving images onto a larger screen. Nonetheless, information technology was the invention of 2 brothers, Auguste and Louis Lumière—photographic goods manufacturers in Lyon, France—that saw the well-nigh commercial success. In 1895, the brothers patented the cinématographe (from which nosotros get the term movie house), a lightweight picture projector that also functioned as a photographic camera and printer. Dissimilar the Edison kinetograph, the cinématographe was lightweight plenty for piece of cake outdoor filming, and over the years the brothers used the camera to have well over 1,000 short films, virtually of which depicted scenes from everyday life. In December 1895, in the basement lounge of the Chiliad Café, Rue des Capucines in Paris, the Lumières held the world's starting time ever commercial film screening, a sequence of about 10 brusk scenes, including the blood brother's starting time film, Workers Leaving the Lumière Manufactory, a segment lasting less than a minute and depicting workers leaving the family'due south photographic instrument factory at the end of the day, as shown in the still frame here in Effigy 8.3 (Encyclopedia of the Age of Industry and Empire).

Assertive that audiences would become bored watching scenes that they could just every bit easily observe on a casual walk around the metropolis, Louis Lumière claimed that the cinema was "an invention without a future (Menand, 2005)," but a demand for motility pictures grew at such a rapid rate that presently representatives of the Lumière visitor were traveling throughout Europe and the world, showing one-half-hour screenings of the company's films. While cinema initially competed with other popular forms of amusement—circuses, vaudeville acts, theater troupes, magic shows, and many others—somewhen it would supersede these various entertainments as the main commercial attraction (Menand, 2005). Inside a year of the Lumières' get-go commercial screening, competing film companies were offering moving-picture acts in music halls and vaudeville theaters across Great Great britain. In the United States, the Edison Company, having purchased the rights to an improved projector that they chosen the Vitascope, held their first film screening in April 1896 at Koster and Bial'south Music Hall in Herald Foursquare, New York City.

Film'due south profound impact on its earliest viewers is difficult to imagine today, inundated as many are past video images. Nevertheless, the sheer volume of reports virtually the early audience's disbelief, delight, and even fear at what they were seeing suggests that viewing a film was an overwhelming experience for many. Spectators gasped at the realistic details in films such as Robert Paul'southward Rough Sea at Dover, and at times people panicked and tried to flee the theater during films in which trains or moving carriages sped toward the audience (Robinson). Even the public's perception of film as a medium was considerably different from the contemporary understanding; the moving paradigm was an improvement upon the photo—a medium with which viewers were already familiar—and this is perhaps why the primeval films documented events in brief segments but didn't tell stories. During this "novelty period" of movie theater, audiences were more interested by the phenomenon of the film projector itself, so vaudeville halls advertised the kind of projector they were using (for example "The Vitascope—Edison'due south Latest Marvel") (Balcanasu, et. al.), rather than the names of the films (Britannica Online).

By the close of the 19th century, as public excitement over the moving flick's novelty gradually wore off, filmmakers were also beginning to experiment with film'southward possibilities as a medium in itself (not simply, as it had been regarded up until and so, as a tool for documentation, analogous to the camera or the phonograph). Technical innovations immune filmmakers like Parisian cinema owner Georges Méliès to experiment with special furnishings that produced seemingly magical transformations on screen: flowers turned into women, people disappeared with puffs of smoke, a man appeared where a woman had simply been standing, and other similar tricks (Robinson).

Non only did Méliès, a former magician, invent the "trick film," which producers in England and the United States began to imitate, just he was besides the one to transform cinema into the narrative medium it is today. Whereas earlier, filmmakers had only ever created unmarried-shot films that lasted a minute or less, Méliès began joining these curt films together to create stories. His 30-scene Trip to the Moon (1902), a film based on a Jules Verne novel, may have been the most widely seen product in movie house's offset decade (Robinson). However, Méliès never developed his technique beyond treating the narrative film as a staged theatrical functioning; his camera, representing the vantage point of an audience facing a phase, never moved during the filming of a scene. In 1912, Méliès released his concluding commercially successful production, The Conquest of the Pole, and from then on, he lost audiences to filmmakers who were experimenting with more than sophisticated techniques (Encyclopedia of Advice and Data).

Figure 8.4

Georges Méliès's Trip to the Moon was one of the first films to incorporate fantasy elements and to employ "fob" filming techniques, both of which heavily influenced hereafter filmmakers.

Craig Duffy – Workers Leaving The Lumiere Mill – CC BY-NC 2.0.

The Nickelodeon Craze (1904–1908)

One of these innovative filmmakers was Edwin Due south. Porter, a projectionist and engineer for the Edison Visitor. Porter's 12-minute moving-picture show, The Great Railroad train Robbery (1903), broke with the stagelike compositions of Méliès-style films through its employ of editing, camera pans, rear projections, and diagonally composed shots that produced a continuity of activeness. Not only did The Great Railroad train Robbery found the realistic narrative as a standard in cinema, it was also the first major box-office hit. Its success paved the manner for the growth of the moving-picture show industry, as investors, recognizing the motion picture's great moneymaking potential, began opening the starting time permanent film theaters around the country.

Known as nickelodeons considering of their v cent admission charge, these early moving picture theaters, often housed in converted storefronts, were especially popular among the working grade of the time, who couldn't afford live theater. Between 1904 and 1908, around 9,000 nickelodeons appeared in the United states of america. It was the nickelodeon'south popularity that established film as a mass entertainment medium (Lexicon of American History).

The "Biz": The Motion Motion picture Industry Emerges

As the demand for movement pictures grew, production companies were created to meet it. At the acme of nickelodeon popularity in 1910 (Britannica Online), there were xx or so major movement movie companies in the Us. However, heated disputes often broke out amid these companies over patent rights and industry command, leading even the most powerful amid them to fear fragmentation that would loosen their hold on the market place (Fielding, 1967). Because of these concerns, the 10 leading companies—including Edison, Biograph, Vitagraph, and others—formed the Movement Picture Patents Visitor (MPPC) in 1908. The MPPC was a merchandise grouping that pooled the near significant motion picture patents and established an exclusive contract between these companies and the Eastman Kodak Company as a supplier of moving picture stock. Also known as the Trust, the MPPC's goal was to standardize the industry and close out competition through monopolistic control. Under the Trust'due south licensing system, only certain licensed companies could participate in the exchange, distribution, and production of moving-picture show at different levels of the industry—a close-out tactic that eventually backfired, leading the excluded, contained distributors to organize in opposition to the Trust (Britannica Online).

The Rise of the Characteristic

In these early years, theaters were nonetheless running single-reel films, which came at a standard length of 1,000 feet, allowing for almost xvi minutes of playing time. Still, companies began to import multiple-reel films from European producers effectually 1907, and the format gained popular acceptance in the Us in 1912 with Louis Mercanton's highly successful Queen Elizabeth, a 3-and-a-half reel "feature," starring the French actress Sarah Bernhardt. As exhibitors began to show more features—as the multiple-reel picture show came to be chosen—they discovered a number of advantages over the single-reel curt. For i affair, audiences saw these longer films as special events and were willing to pay more for access, and because of the popularity of the feature narratives, features generally experienced longer runs in theaters than their single-reel predecessors (Motility Pictures). Additionally, the feature moving picture gained popularity among the center classes, who saw its length as coordinating to the more than "respectable" entertainment of alive theater (Motion Pictures). Following the example of the French film d'art, U.Due south. feature producers oft took their material from sources that would appeal to a wealthier and ameliorate educated audience, such as histories, literature, and stage productions (Robinson).

As it turns out, the characteristic picture was one factor that brought most the eventual downfall of the MPPC. The inflexible structuring of the Trust'southward exhibition and distribution arrangement made the organization resistant to change. When movie studio, and Trust member, Vitagraph began to release features similar A Tale of 2 Cities (1911) and Uncle Tom's Cabin (1910), the Trust forced information technology to showroom the films serially in single-reel showings to proceed with manufacture standards. The MPPC as well underestimated the appeal of the star arrangement, a tendency that began when producers chose famous stage actors similar Mary Pickford and James O'Neill to play the leading roles in their productions and to grace their advertising posters (Robinson). Because of the MPPC'southward inflexibility, contained companies were the just ones able to capitalize on two of import trends that were to become film'south future: single-reel features and star ability. Today, few people would recognize names like Vitagraph or Biograph, merely the independents that outlasted them—Universal, Goldwyn (which would later merge with Metro and Mayer), Play a trick on (later 20th Century Fox), and Paramount (the later version of the Lasky Corporation)—have get household names.

Hollywood

Every bit moviegoing increased in popularity among the middle class, and as the feature films began keeping audiences in their seats for longer periods of time, exhibitors found a need to create more comfortable and richly decorated theater spaces to attract their audiences. These "dream palaces," and then chosen because of their ofttimes lavish embellishments of marble, brass, guilding, and cut drinking glass, not but came to replace the nickelodeon theater, but also created the demand that would atomic number 82 to the Hollywood studio arrangement. Some producers realized that the growing need for new work could just be met if the films were produced on a regular, twelvemonth-round system. However, this was impractical with the current organisation that often relied on outdoor filming and was predominately based in Chicago and New York—two cities whose weather conditions prevented outdoor filming for a significant portion of the year. Different companies attempted filming in warmer locations such equally Florida, Texas, and Cuba, but the identify where producers eventually found the nearly success was a small, industrial suburb of Los Angeles called Hollywood.

Hollywood proved to be an ideal location for a number of reasons. Not only was the climate temperate and sunny twelvemonth-round, simply land was plentiful and inexpensive, and the location allowed close admission to a number of diverse topographies: mountains, lakes, desert, coasts, and forests. By 1915, more than 60 percentage of U.S. film production was centered in Hollywood (Britannica Online).

The Art of Silent Film

While the development of narrative film was largely driven by commercial factors, information technology is besides of import to acknowledge the role of individual artists who turned it into a medium of personal expression. The film of the silent era was generally simplistic in nature; acted in overly animated movements to appoint the eye; and accompanied past live music, played by musicians in the theater, and written titles to create a mood and to narrate a story. Inside the confines of this medium, one filmmaker in particular emerged to transform the silent film into an fine art and to unlock its potential every bit a medium of serious expression and persuasion. D. W. Griffith, who entered the film manufacture as an actor in 1907, quickly moved to a directing role in which he worked closely with his camera crew to experiment with shots, angles, and editing techniques that could raise the emotional intensity of his scenes. He found that by practicing parallel editing, in which a film alternates between 2 or more than scenes of action, he could create an illusion of simultaneity. He could then heighten the tension of the film's drama by alternate between cuts more and more than rapidly until the scenes of activity converged. Griffith used this technique to great effect in his controversial film The Birth of a Nation, which volition be discussed in greater detail subsequently on in this affiliate. Other techniques that Griffith employed to new event included panning shots, through which he was able to establish a sense of scene and to engage his audience more fully in the experience of the film, and tracking shots, or shots that traveled with the motion of a scene (Motion Pictures), which allowed the audience—through the eye of the camera—to participate in the film's action.

MPAA: Combating Censorship

As pic became an increasingly lucrative U.S. industry, prominent manufacture figures similar D. W. Griffith, slapstick comedian/director Charlie Chaplin, and actors Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks grew extremely wealthy and influential. Public attitudes toward stars and toward some stars' extravagant lifestyles were divided, much as they are today: On the one paw, these celebrities were idolized and imitated in pop culture, yet at the aforementioned time, they were criticized for representing a threat, on and off screen, to traditional morals and social order. And much equally it does today, the news media liked to sensationalize the lives of celebrities to sell stories. Comedian Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, who worked alongside future icons Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, was at the center of 1 of the biggest scandals of the silent era. When Arbuckle hosted a marathon party over Labor Day weekend in 1921, 1 of his guests, model Virginia Rapp, was rushed to the hospital, where she later died. Reports of a drunken orgy, rape, and murder surfaced. Following Globe State of war I, the U.s. was in the center of significant social reforms, such as Prohibition. Many feared that movies and their stars could threaten the moral gild of the country. Because of the nature of the law-breaking and the celebrity involved, these fears became inexplicably tied to the Artbuckle case (Motility Pictures). Even though autopsy reports ruled that Rapp had died from causes for which Arbuckle could not be blamed, the comedian was tried (and acquitted) for manslaughter, and his career was ruined.

The Arbuckle matter and a series of other scandals only increased public fears virtually Hollywood's impact. In response to this perceived threat, state and local governments increasingly tried to censor the content of films that depicted crime, violence, and sexually explicit material. Deciding that they needed to protect themselves from government censorship and to foster a more than favorable public image, the major Hollywood studios organized in 1922 to form an association they chosen the Movement Picture Producers and Distributers of America (subsequently renamed the Motion Picture show Clan of America, or MPAA). Among other things, the MPAA instituted a lawmaking of self-censorship for the motion picture industry. Today, the MPAA operates by a voluntary rating system, which means producers tin can voluntarily submit a film for review, which is designed to alert viewers to the historic period-appropriateness of a flick, while still protecting the filmmakers' creative freedom (Motion Movie Association of America).

Silent Film's Demise

In 1925, Warner Bros. was just a pocket-size Hollywood studio looking for opportunities to expand. When representatives from Western Electric offered to sell the studio the rights to a new technology they called Vitaphone, a sound-on-disc system that had failed to capture the interest of any of the manufacture giants, Warner Bros. executives took a chance, predicting that the novelty of talking films might exist a way to make a quick, short-term profit. Little did they conceptualize that their chance would not only establish them every bit a major Hollywood presence but also modify the industry forever.

The pairing of sound with motion pictures was nothing new in itself. Edison, after all, had deputed the kinetoscope to create a visual accompaniment to the phonograph, and many early on theaters had orchestra pits to provide musical accompaniment to their films. Fifty-fifty the smaller picture houses with lower budgets virtually always had an organ or pianoforte. When Warner Bros. purchased Vitaphone technology, it planned to use information technology to provide prerecorded orchestral accompaniment for its films, thereby increasing their marketability to the smaller theaters that didn't have their own orchestra pits (Gochenour, 2000). In 1926, Warner debuted the organization with the release of Don Juan, a costume drama accompanied past a recording of the New York Combo Orchestra; the public responded enthusiastically (Motility Pictures). By 1927, subsequently a $3 million campaign, Warner Bros. had wired more than 150 theaters in the Us, and it released its second sound picture show, The Jazz Singer, in which the actor Al Jolson improvised a few lines of synchronized dialogue and sang six songs. The film was a major breakthrough. Audiences, hearing an thespian speak on screen for the first time, were enchanted (Gochenour). While radio, a new and popular entertainment, had been drawing audiences abroad from the moving-picture show houses for some fourth dimension, with the birth of the "talkie," or talking film, audiences once again returned to the cinema in big numbers, lured past the promise of seeing and hearing their idols perform (Higham, 1973). Past 1929, three-fourths of Hollywood films had some form of sound accompaniment, and by 1930, the silent moving-picture show was a thing of the by (Gochenour).

"I Don't Remember We're in Kansas Anymore": Pic Goes Technicolor

Although the techniques of tinting and hand painting had been available methods for adding colour to films for some time (Georges Méliès, for instance, employed a crew to mitt-paint many of his films), neither method e'er caught on. The hand-painting technique became impractical with the advent of mass-produced picture, and the tinting procedure, which filmmakers discovered would create an interference with the transmission of audio in films, was abandoned with the rising of the talkie. Still, in 1922, Herbert Kalmus'southward Technicolor company introduced a dye-transfer technique that allowed it to produce a full-length film, The Toll of the Sea, in ii primary colors (Gale Virtual Reference Library). Nevertheless, because but ii colors were used, the appearance of The Toll of the Body of water (1922), The Ten Commandments (1923), and other early Technicolor films was non very lifelike. By 1932, Technicolor had designed a three-color system with more realistic results, and for the next 25 years, all color films were produced with this improved organisation. Disney's Three Niggling Pigs (1933) and Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1936) and films with live actors, like MGM's The Magician of Oz (1939) and Gone With the Current of air (1939), experienced early success using Technicolor's three-color method.

Despite the success of certain color films in the 1930s, Hollywood, like the rest of the United States, was feeling the bear upon of the Bang-up Depression, and the expenses of special cameras, crews, and Technicolor lab processing made color films impractical for studios trying to cutting costs. Therefore, information technology wasn't until the terminate of the 1940s that Technicolor would largely readapt the black-and-white motion-picture show (Movement Pictures in Color).

Rising and Fall of the Hollywood Studio

The spike in theater omnipresence that followed the introduction of talking films inverse the economic structure of the movement flick manufacture, bringing virtually some of the largest mergers in industry history. By 1930, 8 studios produced 95 per centum of all American films, and they connected to feel growth even during the Depression. The 5 most influential of these studios—Warner Bros., Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, RKO, 20th Century Fox, and Paramount—were vertically integrated; that is, they controlled every part of the system as information technology related to their films, from the production to release, distribution, and fifty-fifty viewing. Because they endemic theater chains worldwide, these studios controlled which movies exhibitors ran, and because they "owned" a stock of directors, actors, writers, and technical assistants by contract, each studio produced films of a detail grapheme.

The late 1930s and early 1940s are sometimes known as the "Golden Age" of movie house, a time of unparalleled success for the film industry; by 1939, film was the 11th-largest industry in the U.s., and during World State of war Ii, when the U.Southward. economic system was in one case over again flourishing, two-thirds of Americans were attending the theater at least once a calendar week (Britannica Online). Some of the nigh acclaimed movies in history were released during this period, including Citizen Kane and The Grapes of Wrath. Yet, postwar inflation, a temporary loss of fundamental foreign markets, the advent of the television, and other factors combined to bring that rapid growth to an end. In 1948, the case of the United states v. Paramount Pictures—mandating competition and forcing the studios to relinquish control over theater chains—dealt the final devastating blow from which the studio system would never recover. Control of the major studios reverted to Wall Street, where the studios were eventually captivated by multinational corporations, and the powerful studio heads lost the influence they had held for nearly 30 years (Baers, 2000).

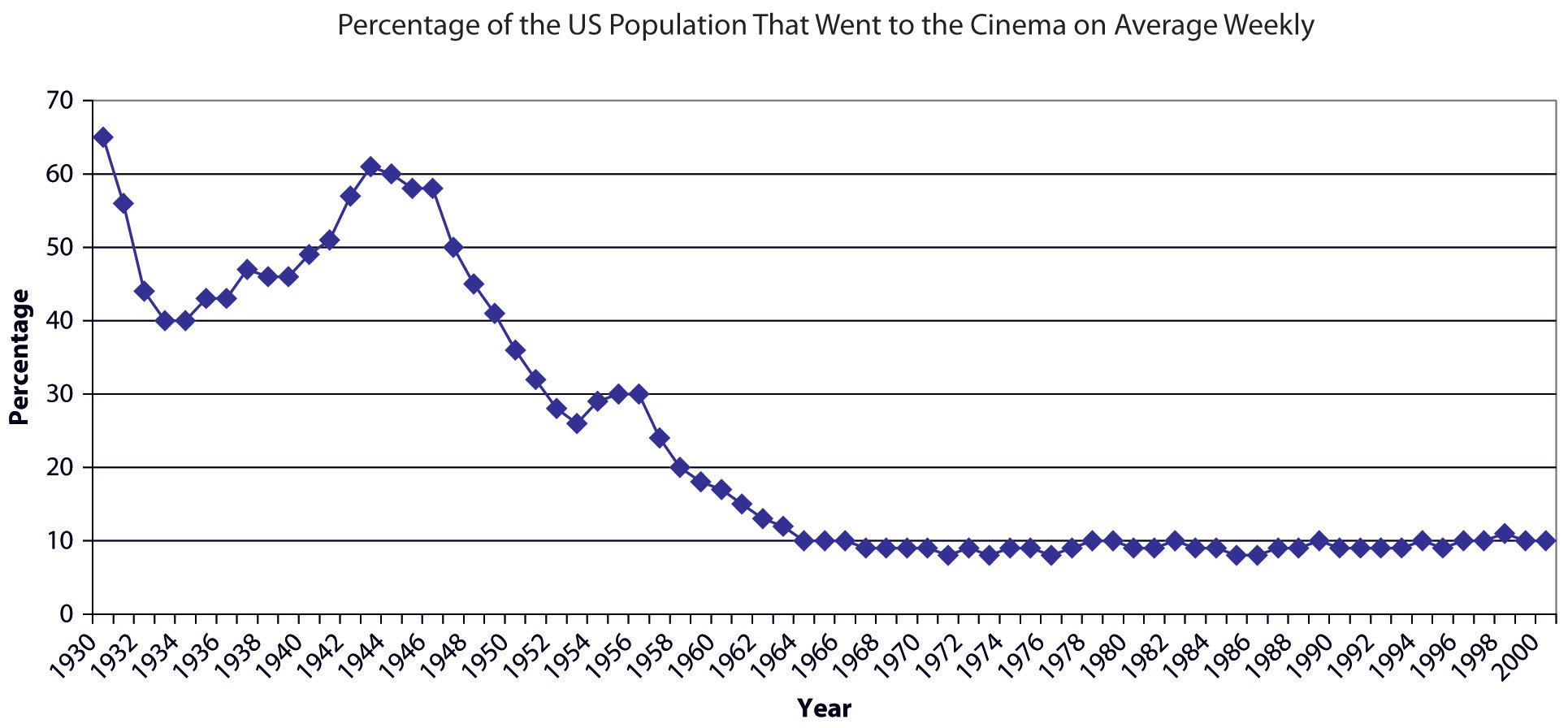

Figure 8.v

Rising and Refuse of Pic Viewing During Hollywood's "Aureate Age"

Graph from Pautz, Michelle C. 2002. The Turn down in Average Weekly Cinema Attendance: 1930–2000. Problems in Political Economy, 11 (Summer): 54–65.

Mail–World War Ii: Television Presents a Threat

While economic factors and antitrust legislation played key roles in the decline of the studio arrangement, possibly the most of import gene in that reject was the appearance of the television. Given the opportunity to watch "movies" from the condolement of their ain homes, the millions of Americans who endemic a television by the early on 1950s were attending the movie theater far less regularly than they had just several years earlier (Motion Pictures). In an attempt to win dorsum diminishing audiences, studios did their all-time to exploit the greatest advantages film held over telly. For one thing, idiot box dissemination in the 1950s was all in black and white, whereas the picture show industry had the advantage of color. While producing a color film was still an expensive undertaking in the late 1940s, a couple of changes occurred in the industry in the early 1950s to brand color not only more than affordable, merely more realistic in its appearance. In 1950, as the result of antitrust legislation, Technicolor lost its monopoly on the color motion picture manufacture, allowing other providers to offer more competitive pricing on filming and processing services. At the aforementioned time, Kodak came out with a multilayer picture show stock that made it possible to employ more affordable cameras and to produce a higher quality image. Kodak'due south Eastmancolor option was an integral component in converting the industry to color. In the tardily 1940s, just 12 percent of features were in color; however, by 1954 (after the release of Kodak Eastmancolor) more than 50 percent of movies were in color (Britannica Online).

Another clear reward on which filmmakers tried to capitalize was the sheer size of the cinema experience. With the release of the epic biblical film The Robe in 1953, 20th Century Fox introduced the method that would soon exist adopted by nearly every studio in Hollywood: a technology that immune filmmakers to clasp a wide-angle prototype onto conventional 35-mm motion picture stock, thereby increasing the aspect ratio (the ratio of a screen'south width to its height) of their images. This wide-screen format increased the immersive quality of the theater experience. Nonetheless, even with these advancements, moving-picture show attendance never over again reached the record numbers it experienced in 1946, at the pinnacle of the Golden Age of Hollywood (Britannica Online).

Mass Entertainment, Mass Paranoia: HUAC and the Hollywood Blacklist

The Cold State of war with the Soviet Union began in 1947, and with it came the widespread fearfulness of communism, not only from the exterior, but equally from within. To undermine this perceived threat, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) commenced investigations to locate communist sympathizers in America who were suspected of conducting espionage for the Soviet Union. In the highly conservative and paranoid temper of the time, Hollywood, the source of a mass-cultural medium, came under fire in response to fears that destructive, communist messages were existence embedded in films. In Nov 1947, more than 100 people in the movie business were called to testify before the HUAC about their and their colleagues' involvement with communist affairs. Of those investigated, ten in particular refused to cooperate with the committee's questions. These 10, later known as the Hollywood Ten, were fired from their jobs and sentenced to serve up to a year in prison house. The studios, already slipping in influence and profit, were eager to cooperate in lodge to relieve themselves, and a number of producers signed an agreement stating that no communists would work in Hollywood.

The hearings, which recommenced in 1951 with the rise of Senator Joseph McCarthy'due south influence, turned into a kind of witch hunt as witnesses were asked to testify against their assembly, and a blacklist of suspected communists evolved. Over 324 individuals lost their jobs in the film industry as a result of blacklisting (the denial of work in a certain field or manufacture) and HUAC investigations (Georgakas, 2004; Mills, 2007; Dressler, et. al., 2005).

Down With the Establishment: Youth Culture of the 1960s and 1970s

Movies of the late 1960s began attracting a younger demographic, as a growing number of young people were drawn in by films like Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969), Stanley Kubrick'south 2001: A Infinite Odyssey (1968), Arthur Penn'due south Bonnie and Clyde (1967), and Dennis Hopper's Easy Passenger (1969)—all revolutionary in their genres—that displayed a sentiment of unrest toward conventional social orders and included some of the earliest instances of realistic and brutal violence in flick. These iv films in particular grossed and so much money at the box offices that producers began churning out low-budget copycats to depict in a new, assisting market (Move Pictures). While this led to a rise in youth-culture films, few of them saw great success. However, the new liberal attitudes toward depictions of sex and violence in these films represented a sea of change in the movie industry that manifested in many movies of the 1970s, including Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather (1972), William Friedkin's The Exorcist (1973), and Steven Spielberg's Jaws (1975), all three of which saw corking financial success (Britannica Online; Belton, 1994).

Blockbusters, Knockoffs, and Sequels

In the 1970s, with the rise of piece of work by Coppola, Spielberg, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese, and others, a new breed of director emerged. These directors were young and flick-school educated, and they contributed a sense of professionalism, sophistication, and technical mastery to their work, leading to a wave of blockbuster productions, including Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), Star Wars (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), and E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial (1982). The computer-generated special effects that were available at this fourth dimension also contributed to the success of a number of large-budget productions. In response to these and several earlier blockbusters, movie production and marketing techniques also began to shift, with studios investing more than coin in fewer films in the hopes of producing more than big successes. For the kickoff time, the hefty sums producers and distributers invested didn't get to production costs alone; distributers were discovering the benefits of TV and radio advertising and finding that doubling their advertising costs could increase profits as much as three or four times over. With the opening of Jaws, one of the five top-grossing films of the decade (and the highest grossing film of all time until the release of Star Wars in 1977), Hollywood embraced the wide-release method of movie distribution, abandoning the release methods of earlier decades, in which a motion picture would debut in only a handful of select theaters in major cities before information technology became gradually available to mass audiences. Jaws was released in 600 theaters simultaneously, and the large-budget films that followed came out in anywhere from 800 to two,000 theaters nationwide on their opening weekends (Belton; Hanson & Garcia-Myers, 2000).

The major Hollywood studios of the late 1970s and early 1980s, now run by international corporations, tended to favor the conservative gamble of the tried and truthful, and every bit a consequence, the period saw an unprecedented number of high-budget sequels—as in the Star Wars, Indiana Jones, and Godfather films—as well as imitations and adaptations of earlier successful material, such every bit the plethora of "slasher" films that followed the success of the 1979 thriller Halloween. Additionally, corporations sought revenue sources beyond the picture palace, looking to the video and cable releases of their films. Introduced in 1975, the VCR became nearly ubiquitous in American homes by 1998 with 88.ix million households owning the appliance (Rosen & Meier, 2000). Cable television's growth was slower, but ownership of VCRs gave people a new reason to subscribe, and cable subsequently expanded as well (Rogers). And the newly introduced concept of film-based merchandise (toys, games, books, etc.) immune companies to increase profits fifty-fifty more than.

The 1990s and Across

The 1990s saw the rise of two divergent strands of cinema: the technically spectacular blockbuster with special, computer-generated furnishings and the independent, depression-budget motion-picture show. The capabilities of special furnishings were enhanced when studios began manipulating film digitally. Early examples of this technology can be seen in Terminator 2: Judgment Mean solar day (1991) and Jurassic Park (1993). Films with an ballsy scope—Independence Twenty-four hour period (1996), Titanic (1997), and The Matrix (1999)—also employed a range of computer-animation techniques and special effects to wow audiences and to draw more viewers to the large screen. Toy Story (1995), the first fully computer-blithe flick, and those that came after it, such as Antz (1998), A Issues'due south Life (1998), and Toy Story 2 (1999), displayed the improved capabilities of reckoner-generated animation (Sedman, 2000). At the aforementioned fourth dimension, independent directors and producers, such as the Coen brothers and Spike Jonze, experienced an increased popularity, oftentimes for lower-budget films that audiences were more than likely to watch on video at home (Britannica Online). A prime example of this is the 1996 Academy Awards program, when contained films dominated the All-time Picture category. Only ane motion-picture show from a big pic studio was nominated—Jerry Maguire—while the rest were independent films. The growth of both independent movies and special-furnishings-laden blockbusters continues to the present twenty-four hours. You will read more virtually current problems and trends and the futurity of the movie industry later on in this chapter.

Cardinal Takeaways

- The concept of the motion picture was first introduced to a mass audience through Thomas Edison's kinetoscope in 1891. However, it wasn't until the Lumière brothers released the cinématographe in 1895 that movement pictures were projected for audition viewing. In the Us, film established itself every bit a popular form of amusement with the nickelodeon theater in the 1910s.

- The release of The Jazz Vocalist in 1927 marked the birth of the talking movie, and past 1930 silent film was a thing of the past. Technicolor emerged for film effectually the aforementioned time and found early success with movies like The Magician of Oz and Gone With the Air current. Yet, people would continue to make films in blackness and white until the late 1950s.

- By 1915 near of the major pic studios had moved to Hollywood. During the Gilt Age of Hollywood, these major studios controlled every aspect of the moving-picture show manufacture, and the films they produced drew crowds to theaters in numbers that have all the same not been surpassed. After World War II, the studio system declined equally a result of antitrust legislation that took power abroad from studios and of the invention of the tv set.

- During the 1960s and 1970s, in that location was a rise in films—including Bonnie and Clyde, The Wild Agglomeration, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Easy Rider—that historic the emerging youth culture and a rejection of the conservatism of the previous decades. This also led to looser attitudes toward depictions of sexuality and violence in film. The 1970s and 1980s saw the rise of the blockbuster, with films like Jaws, Star Wars, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and The Godfather.

- The adoption of the VCR by most households in the 1980s reduced audiences at movie theaters but opened a new mass market place of home movie viewers. Improvements in estimator animation led to more special effects in flick during the 1990s with movies like The Matrix, Jurassic Park, and the first fully computer-blithe picture, Toy Story.

Exercises

Identify four films that you would consider to be representative of major developments in the manufacture and in flick as a medium that were outlined in this section. Imagine you are using these films to explain movie history to a friend. Provide a detailed explanation of why each of these films represents meaning changes in attitudes, engineering science, or trends and situate each in the overall context of movie's development. Consider the following questions:

- How did this movie influence the pic industry?

- What has been the lasting touch of this movie on the film industry?

- How was the film industry and engineering different before this film?

References

Baers, Michael. "Studio Organization," in St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Civilisation, ed. Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast (Detroit: St. James Press, 2000), vol. 4, 565.

Balcanasu, Andrei Ionut, Sergey 5. Smagin, and Stephanie Grand. Thrift, "Edison and the Lumiere Brothers," Cartoons and Movie house of the 20th Century, http://library.thinkquest.org/C0118600/index.phtml?menu=en%3B1%3Bci1001.html.

Belton, American Cinema/American Culture, 305.

Belton, John. American Cinema/American Culture. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1994), 284–290.

Britannica Online, s.5. "History of the Motion Picture".

Britannica Online, south.v. "Kinetoscope," http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/318211/Kinetoscope/318211main/Article.

Britannica Online, s.v. "nickelodeon."

Britannica Online. due south.v. "History of the Motion Picture." http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/394161/history-of-the-motion-picture show; Robinson, From Peep Show to Palace, 45, 53.

British Movie Classics, "The Kinetoscope," British Movie Classics, http://www.britishmovieclassics.com/thekinetoscope.php.

Dictionary of American History, 3rd ed., s.v. "Nickelodeon," past Ryan F. Holznagel, Gale Virtual Reference Library.

Dresler, Kathleen, Kari Lewis, Tiffany Schoser and Cathy Nordine, "The Hollywood 10," Dalton Trumbo, 2005, http://www.mcpld.org/trumbo/WebPages/hollywoodten.htm.

Encyclopedia of Communication and Information (New York: MacMillan Reference USA, 2002), s.v. "Méliès, Georges," by Ted C. Jones, Gale Virtual Reference Library.

Encyclopedia of the Age of Manufacture and Empire, southward.5. "Movie house."

Fielding, Raymond A Technological History of Movement Pictures and Television (Berkeley: California Univ. Printing, 1967) 21.

Gale Virtual Reference Library, "Move Pictures in Colour," in American Decades, ed. Judith Due south. Baughman and others, vol. three, Gale Virtual Reference Library.

Gale Virtual Reference Library, Europe 1789–1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of Industry and Empire, vol. 1, south.five. "Cinema," by Alan Williams, Gale Virtual Reference Library.

Georgakas, Dan. "Hollywood Blacklist," in Encyclopedia of the American Left, ed. Mari Jo Buhle, Paul Buhle, and Dan Georgakas, 2004, http://writing.upenn.edu/~afilreis/50s/blacklist.html.

Gochenour, "Birth of the 'Talkies,'" 578.

Gochenour, Phil. "Birth of the 'Talkies': The Development of Synchronized Audio for Move Pictures," in Science and Its Times, vol. 6, 1900–1950, ed. Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer (Detroit: Gale, 2000), 577.

Hanson, Steve and Sandra Garcia-Myers, "Blockbusters," in St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Civilization, ed. Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast (Detroit: St. James Press, 2000), vol. i, 282.

Higham, Charles. The Fine art of the American Movie: 1900–1971. (Garden Metropolis: Doubleday & Visitor, 1973), 85.

Menand, Louis "Gross Points," New Yorker, February 7, 2005, http://www.newyorker.com/annal/2005/02/07/050207crat_atlarge.

Mills, Michael. "Blacklist: A Different Wait at the 1947 HUAC Hearings," Modern Times, 2007, http://www.moderntimes.com/blacklist/.

Move Picture Association of America, "History of the MPAA," http://world wide web.mpaa.org/about/history.

Motion Pictures in Color, "Movement Pictures in Color."

Motion Pictures, "Griffith," Motility Pictures, http://www.uv.es/EBRIT/macro/macro_5004_39_6.html#0011.

Motion Pictures, "Post World War I U.s.a. Picture palace," Motility Pictures, http://www.uv.es/EBRIT/macro/macro_5004_39_10.html#0015.

Move Pictures, "Pre Earth War Ii Audio Era: Introduction of Sound," Motion Pictures, http://world wide web.uv.es/EBRIT/macro/macro_5004_39_11.html#0017.

Motion Pictures, "Pre Earth-War I US Cinema," Movement Pictures: The Silent Characteristic: 1910-27, http://www.uv.es/EBRIT/macro/macro_5004_39_4.html#0009.

Motility Pictures, "Recent Trends in US Cinema," Motion Pictures, http://www.uv.es/EBRIT/macro/macro_5004_39_37.html#0045.

Motion Pictures, "The State of war Years and Post World State of war II Trends: Turn down of the Hollywood Studios," Motion Pictures, http://www.uv.es/EBRIT/macro/macro_5004_39_24.html#0030.

Robinson, From Peep Evidence to Palace, 135, 144.

Robinson, From Peep Show to Palace, 63.

Robinson, From Peep Show to Palace, 74–75; Encyclopedia of the Age of Industry and Empire, due south.v. "Cinema."

Robinson, David. From Peep Show to Palace: The Nativity of American Film (New York: Columbia Academy Press, 1994), 43–44.

Rogers, Everett. "Video is Hither to Stay," Heart for Media Literacy, http://www.medialit.org/reading-room/video-hither-stay.

Rosen, Karen and Alan Meier, "Ability Measurements and National Free energy Consumption of Televisions and Video Cassette Recorders in the USA," Free energy, 25, no. 3 (2000), 220.

Sedman, David. "Motion picture Industry, Applied science of," in Encyclopedia of Communication and Data, ed. Jorge Reina Schement (New York: MacMillan Reference, 2000), vol. 1, 340.

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/mediaandculture/chapter/8-2-the-history-of-movies/

0 Response to "in the beginning, what was the major challenge related to placing digital images on cd media?"

Post a Comment